The Lydiard Method

Disclaimer: while many of Lydiard’s principles have been scientifically proven and are used in today’s training methods, certain aspects have been disproven. For example, Lydiard strongly opposed runners lifting weights; we now know strength work can be an excellent complement to running. It is always wise to consult a coach before embarking on a training plan, and as such, this article is intended for entertainment purposes only.

Arthur Lydiard is widely regarded as history’s most important running coach. His methods have been applied by athletes around the world, and his jogging revolution transformed running from an obscure pursuit to the world’s most practised sport. His training philosophy, which greatly informs modern distance running coaching, was built around five unwavering principles: maximising aerobic capacity, feelings-based training, response-regulated recovery, correct timing, and the sequential development of energy systems. Continue on to learn more about these principles or click here to read about Lydiard’s rise to the top of the running world.

Maximising Aerobic Capacity

In an era where interval training was king, Lydiard prioritised aerobic conditioning, which involved running for long periods at a comfortable pace. His theory was simple: when racing anything further than 800m, you spend most of your time using your aerobic system for energy. Therefore, it makes sense that you should spend most of your training hours working on your aerobic system.

Aerobic running can be likened to a happy childhood home: you stay there until you are mature enough to leave and return to it for rest and recuperation. This type of training conditions your body to deal with all other types of training and can be considered the base upon which your fitness can be built.

Four of Arthur Lydiard’s athletes training on the infamous Waiatarua Loop

Feelings-Based Training

Lydiard championed the internal connection between mind and body and believed that the further and more often you run, the stronger this connection will become. A vastly underrated aspect of training, this intrinsic relationship allows athletes to fend off injury, push to their limits, and ultimately maintain the consistency required for success.

Lydiard fostered this ability in his athletes by prescribing feelings-based training, as opposed to specific pace or distance goals. For example, on a recovery day, he would instruct his athletes to run at half-effort, whereas an interval session in the lead-up to a big race may be run at nine-tenths effort. By training to feel rather than specific external metrics, his athletes could get the most out of their training: there is no point pushing a high pace if you feel like you’re getting sick or running too slowly on a day when you feel fresh.

Arthur Lydiard (R) and his most successful athlete, Peter Snell (L), who won three gold medals for New Zealand across the 1960 and 1964 Olympic Games

Response-Regulated Recovery

Training can be defined as specific stress applied to the body to invoke a corresponding adaptation. A workout causes a temporary breakdown in the body (catabolic phase), which is followed by a period of recovery, during which the body rebuilds itself so as to better withstand the stress it has just endured (anabolic phase).

This cycle reveals what is perhaps a counterintuitive idea at first: that the benefits of training are realised not in the workout, but in the recovery. Injury, burnout, and a plateau in performance are often the result of a mismatch between the catabolic and anabolic phases, and typically, this imbalance comes from inadequate recovery.

While Lydiard was notorious for pushing his runners to their limits, he was always mindful of avoiding overtraining. Incorporating a long base phase to adapt the body, using a feelings-based training approach, and adjusting workouts according to an athlete’s recovery response was his recipe for ensuring he didn’t tip his athletes over their breaking points. What Lydiard discovered, and what coaches worldwide must recognise, is that the art of good training calls for an accurate assessment of which side of the adaption curve an athlete is on – catabolic or anabolic – and prescribing training appropriately.

Arthur Lydiard competes for New Zealand on the roads

Correct Timing

The Lydiard method is built around either a goal race or racing period, for which peaking at the correct time is essential. To ensure an athlete performs most optimally during their key event, a Lydiard training program is always written backwards from the goal, allotting appropriate time to each phase.

There is a story told about Lydiard and his athletes at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. In front of their competitors, “Arthur’s Boys” ran an impressive 20 x 400m session. The following day, one of their Canadian rivals arrived at the track with his coach and ran the same session while the New Zealand squad spectated and even cheered him on as he ran each interval faster than the last. When the workout ended, a reporter asked Lydiard what he thought of the session. With a cheeky grin, he replied, “I think it was the last nail in the coffin.”

“But your boys ran the same session yesterday.”

“Yes, but my boys needed it.”

In the coming days, Peter Snell defended his 800m title from 1960 and picked up the 1500m to go with it, while countryman John Davies also medalled in the 1500m. Meanwhile, the Canadian – who had run a faster session than the New Zealanders – was out in the heats.

This anecdote demonstrates how peaking at the correct time is vital to maximising performance, and that good and bad sessions can look exactly the same on paper. Workouts in isolation mean very little; it is their contextual application to the advancement of an athlete’s goals that is important.

New Zealand athletes Peter Snell (M) and John Davies (R) celebrate their medals at the 1964 Olympic Games

Sequential Development of Energy Systems

Lydiard’s training method involved developing the different energy systems of an athlete across four distinct, sequential stages. He designed his programs so that only once one phase had been completed was an athlete ready for the training demands of the next.

Phase One: Aerobic Conditioning

The Lydiard training model is often likened to a pyramid; the wider the base of that pyramid, the higher and stronger you can build it. In terms of your energy systems, aerobic conditioning serves as your base. For Lydiard, key workouts in the aerobic phase involved periods of long, steady running, typically three times a week, where the goal was to never feel anything more than “pleasantly tired.”

Phase Two: Hill Training and Speed Development

Phase two is split into two smaller stages and covers most of the anaerobic work performed in a complete training cycle. It is worth noting that the success of the first phase heavily dictates the effectiveness of the second: the greater your aerobic steady state, the more productive your anaerobic training will be. The first part of phase two revolves around a circuit that includes bounding uphill, running quickly downhill, and sprinting. Completed three times per week, this type of workout improves running economy by developing power and flexibility. The second part of phase two sees a shift to traditional interval training, typically performed on a track. The objective of the entire phase is to create an oxygen debt in workouts that stimulates the metabolism and builds a buffer against fatigue in the athlete.

Phase Three: Sharpening

The sharpening phase provides an opportunity for athletes to test their strengths and weaknesses in preparation for their goal race/s. A combination of long runs, time trials, fartleks (interchanging bouts of fast and slow running), and short interval work expose an athlete’s weaknesses and provide information crucial to improving their racing ability. Once these performance indicators have been identified, the remaining weeks are used to target the appropriate areas.

Phase Four: Tapering and Rest

The final 10 days before a goal race are reserved for “freshening up”, as Lydiard described. While the frequency of training is unchanged, the intensity and duration of workouts are lowered in order to maximise an athlete’s physical and mental reserves for race day.

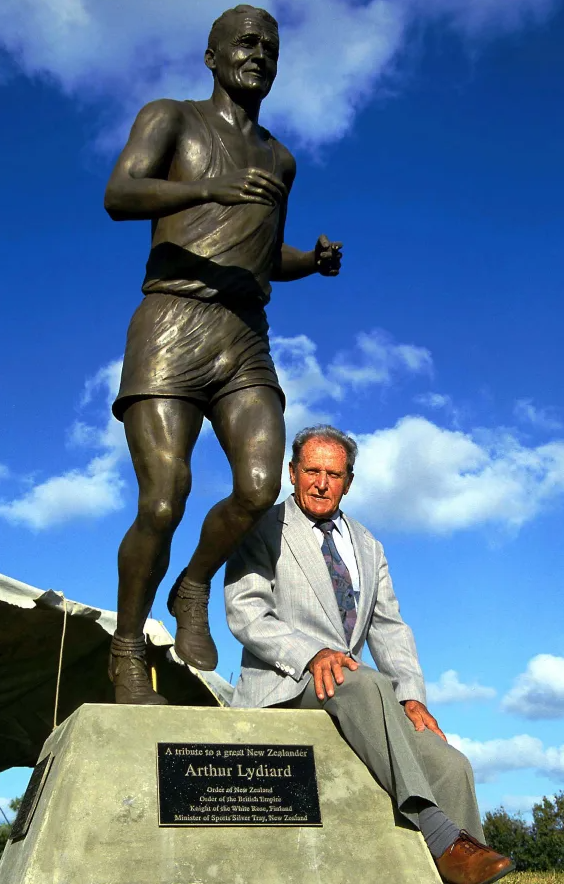

Arthur Lydiard poses in front of his statue in Auckland

When Lydiard was asked which part of the training was most valuable, he replied:

“Everything: who would want to eat a cake half-baked?”

Indeed, the brilliance of Lydiard’s model lies in the holistic approach that allows a runner to develop fully. By sequentially increasing the capacity of each system that contributes to an athlete’s ability, the Lydiard method ensures a runner can perform to their highest potential on race day.